I have been a Business Development Manager for InfraCo Africa for just under four years and love the variety of the job. In Business Development, we can explore new and emerging technologies across multiple sectors and geographies. My background and passion is energy. In this sector, we have the scope to think big, challenging traditional approaches and pioneering solutions, crowding in private sector finance and expertise to make it happen.

My own specialism, an area of ever-increasing focus for InfraCo Africa and the wider PIDG, is off-grid energy. Off-grid developments are vital to reaching remote rural areas swiftly, while displacing polluting fossil fuel alternatives. InfraCo Africa was at the vanguard of off-grid energy, commissioning a 1.6MW solar-thermal plant on Bugala Island, Uganda in 2015 as part of its multi-sector Kalangala Infrastructure Services project. InfraCo Africa has since supported containerised solar distributed power companies in Tanzania and Zambia and we are currently rolling out the ambitious Sierra Leone Mini-grid project, a project I originated in Business Development and one that is set to become the 2nd largest utility in Sierra Leone.

-

Pioneering off grid energy on Bugala Island, Uganda -

Delivering clean energy across rural Sierra Leone

So what are we up against?

I live in Nairobi, a bustling metropolis of blazing lights that can be seen from passing aircraft. Yet such access to power, a key driver of economic development and opportunities, largely drops away at the city boundary. In Kenya, as in many other African countries, access to power is not universal. It is patchy and many homes and businesses, particularly those in remote rural areas, still rely on wood, kerosene lamps and expensive generators for their basic cooking and lighting needs.

Within off-grid, mini-grids have a vital role to play in delivering on the ambitions of SDG7: Clean Energy Access for All by 2030 but to do this, there needs to be a step change to achieve the scale of investment required.

To put this into perspective, the World Bank recently estimated that 490 million people across the world would be best served, at least cost, by the deployment of 210,000 mini-grids at a cost of US$220 billion.[i] The investments made by InfraCo Africa and PowerGen Renewable Energy in 2020, totalled approximately US$10 million and will deliver clean electricity through 40 new mini-grids. This investment is one of the largest in the sub-Saharan mini-grid sector to date, illustrating the scale of the challenge ahead of us. To unlock the sector and achieve scale, at affordable prices to the end consumer, while ensuring reliable returns to the private sector, there are a number of challenges that the sector needs to overcome.

Ultimately, if we are able address these challenges and reduce the risks to investors, access to finance will increase and over time the cost of capital should come down. Alongside falling costs of solar equipment and batteries, as well as the economies of scale afforded to larger projects, this should result in wider deployment of mini-grids at a lower cost to the end consumer.

-

Lighting rural healthcare clinics -

Driving more profitable businesses -

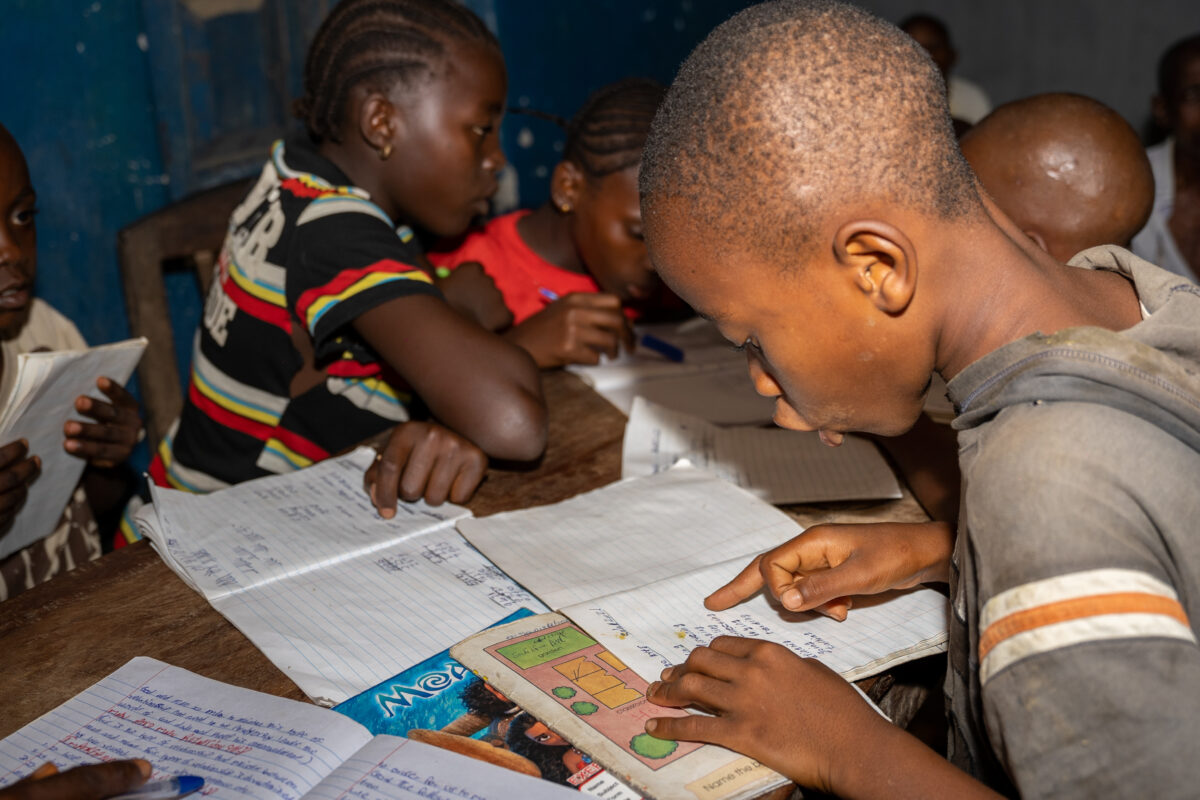

Maximising opportunities for learning

To make this happen, government support is key. Mini-grid developers need clear policies and regulation that support cost-reflective tariffs and access to electrification plans, which set out where national grid extensions will take place and when. Without these, it is difficult to build clear business plans and even harder to attract the necessary investment.

In the short to medium term, there is a need for effective subsidy programmes. There has been some promising progress made; however, programmes are often complex, costly and take a long time to administer. Results Based Financing models are currently leading the way, and I am encouraged by the creation and roll out of the Universal Energy Facility.

Once customers are connected, long term economic development is not a given. It is key that providers of power work closely with mini-grid customers, if we are to see the true benefits of clean power and economic growth. The COVID-19 pandemic will undoubtedly prompt a greater focus on renewable energy for healthcare and there are exciting logistics opportunities here too as we seek to address the issue of getting vaccines to people. These could include cold storage, modular power to be located near remote clinics and refrigerated supply chains. However, for wider economic growth, we must promote productive use of energy, which includes amongst other things, access to affordable appliances, water pumping and purification and solar-powered irrigation technologies.

-

Pumping and purifying water -

Making appliances affordable -

Powering irrigation systems

Finally, as revenues are in local currency, there is a need for long term local currency financing to mitigate foreign currency risk. Our sister PIDG company, GuarantCo, has a mandate to mobilise long-term local currency finance and together, by leveraging the power of the PIDG, we hope to be able to catalyse the sector and attract more private sector capital.

Despite the very real challenges, I have seen a shift in ambition over the past few years and a growing buzz around mini-grids.

Mini-grids in remote rural areas are now seen as a real solution to provide access to power, and we are starting to see mini-grids forming part of national electrification plans alongside other off-grid technologies, more traditional large-scale power projects and grid densification.

The sector is also becoming increasingly coordinated; with the Mini-Grids Partnership, the Mini-grid Funders Group, the Africa Mini-Grid Developers Association (AMDA) and the more recent establishment of the Alliance for Rural Electrification (ARE) finance working group. We have also been impressed by CrossBoundary Energy Access’s ambition to open-source its learning.

On the developer side too, we see increasing ambition. Projects often involve >10,000 connections where 10 years ago 1-2,000 was seen as a maximum. This is largely a reflection of the improvements we have seen in policy and regulatory frameworks and in greater access to financing. Where developers used to focus on one country, more experienced developers are now setting their sights on a portfolio of countries. Enabling them to attract larger ticket sizes, reducing the friction and cost of country by country fund raising and allowing them to focus on building minigrids. At this scale and with a portfolio approach, there is a greater opportunity to manage risks across countries and consider risk mitigation tools that become more affordable at this scale.

This is an exciting time to be a part of the industry: working with our partners and developers to steer a climate-focused, sustainable course out of the COVID-19 pandemic. With increasing government and donor engagement and new options emerging to enable developers to access Results Based Financing, Africa’s mini-grid sector looks set to flourish.

[i] Technical Paper: Mini Grids for Half a Billion People : Market Outlook and Handbook for Decision Makers, ESMAP 2019: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31926

Leave a Reply

Related projects

Uganda: Kalangala Infrastructure Services I & II

Making connections for a brighter future

A pioneering mixed utility on Bugala Island which operates two roll-on roll-off ferries, upgraded 66km of road, distributes clean water and developed a 1.6MW hybrid solar-diesel power plant.